For close to a decade, separatist groups in Cameroon’s Anglophone regions have carried out systematic and widespread attacks on students, teachers, and schools. Now, for the first time ever, some separatist fighters who dropped their weapons are returning to attend classes in schools they once attacked. The separatist war is in progress and there is no end in sight.

By Arison Tamfu

September 30, 2025: The morning sun rises over Buea, the chief town of Cameroon’s Southwest region. But instead of the usual chatter of pupils, silence cloaks shuttered classrooms. Teachers and students remain indoors, forced by separatist fighters enforcing a month-long lockdown aimed at disrupting the new school term and the presidential election scheduled for October 12.

It is the new normal in Cameroon’s two English-speaking regions of Northwest and Southwest where schools that are designed as havens for children to grow, learn and make friends, now inspire fear.

For close to a decade, students and teachers have borne the brunt of an armed separatist conflict, which pits the country’s largely French-speaking government against Anglophone fighters demanding independence for the two regions.

More than 6,000 people, including students and teachers, have so far been killed in the conflict, according to local human rights groups.

In 2016, lawyers and teachers called for school boycott as part of peaceful protests aimed at preserving the two regions’ distinct English educational and legal systems. A severe army crackdown on the protesters triggered an armed rebellion, resolute to create an independent nation in the regions.

Yet, though popular at first, the school boycott quickly lost support as separatist militias began destroying schools and killing teachers who continued working.

In June, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) reported that the school boycott had gravely disrupted learning since then: 41 percent of schools are still non-functional, leaving nearly 224,000 children out of class.

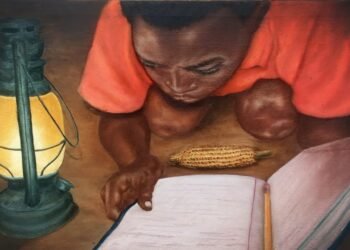

Among those who once helped impose such disruptions is Malu (not his real name), a former separatist fighter now determined to rewrite his story.

Recruited just days before his 20th birthday, he spent 10 months with a separatist militia that operates mainly along the southwestern border with Nigeria.

He was given a uniform and weeks of basic firearms training before he and other recruits faced an initiation test. They were told they would be killed if they failed to open fire when ordered to.

“That was in 2021. The [separatist] commander said we were going to attack a school,” he recalls.

In the early morning of November 24, 2021, he and other fighters went to a government school in Ekondo Titi locality of Southwest region, opened fire on students and teachers who were learning.

“We just started shooting indiscriminately. I was so scared and fired my gun like a crazy person…” he says.

He still thinks about the children’s drawings soaked in blood, littered across the floor and a French teacher, lying dead on the floor. Amid the wreckage surrounding the teacher were books and papers, smeared in blood. Four students and a teacher were killed in the attack that day, according to local officials.

“It (the attack) distressed me for a long time. When I was sleeping, I will hear the screams of the children and see blood. Why schools? I could not comprehend why innocent children studying should be our target,” he says.

It was then he realized he had made a mistake and decided to run away. He escaped to Nigeria where he is now pursuing a degree in history.

He says he has turned his back on the violence for good. Now 24, he is enjoying school for the first time.

“I never thought I will go to school again until I arrived in Nigeria and made up my mind to return to school. I want to become a teacher,” he said. “It’s really good because school is helping to rehabilitate me and to get over what I went through,” Malu says.

For Okha Clovis Naseri, another former separatist fighter, one of the hardest things to accept as a fighter was the kidnapping and shooting of schoolchildren and teachers.

His breaking point came the day he refused an order from a separatist commander to attack a school.

“I asked the commander: ‘when we go there and shoot what will happen to those children?’ I told him that, instead of protecting children, if we attacked them, then we have failed in our mission of fighting for independence,” he says.

Naseri joined the separatist armed group at 17. After nearly two years in combat, he surrendered to Cameroonian authorities, disillusioned by what he called “persistent deception from separatist leaders and deviation from the original mission.”

He spent 18 months in a state-run rehabilitation center, reflecting on his past and what his future could look like. “Then I went to the university, studied logistics and transport management, and graduated with an upper grade,” says the now 25-year-old. “I think I will continue my studies and see what I can do for children’s education.”

Another ex-fighter, Ateasong Beltus Tajoah, has also rebuilt his life around education. He now teaches logic and philosophy at a secondary school in Dschang, a town in Cameroon’s West region. Yet his childhood dream of becoming a teacher was almost derailed in 2017, when, at just 22, he joined the separatist militia.

“We attacked schools, teachers, and students. We used classrooms as our camps. We turned schools into weapons of war, imposing boycotts to hurt the government,” he says.

After laying down arms, Tajoah returned to his studies, pursued philosophy, and eventually earned a master’s degree. Now 31, he shares his past with his students as a warning.

“The students I teach today can never fall into the same trap I fell into because I tell them my story. Despite once fighting, I now encourage the same children to go to school. I don’t just preach it — I practice it,” he says.

Naseri, Tajoah and Malu are now outspoken advocates for education. “We use social media to sensitize the population and preach peace and unity,” says Naseri.

Their journeys reflect a wider shift. According to Cameroonian authorities, more than 2,000 separatist fighters have surrendered since peaceful protests turned into an armed conflict in 2017. Over half have either resumed school or taken up vocational training — progress officials view as a milestone in restoring peace and safeguarding the right to education.

Teachers believe the rebels’ strategy of targeting schools has ultimately backfired.

“Education is a fundamental tool for children’s progress and future. To use it as a political weapon was a mistake on the part of the separatists,” says Richard Ndifor, an educator. “It is encouraging to see former fighters returning to attend classes in schools they once attacked. This sends a strong message: those who attack education are not fighting the regime, they are fighting the future of young Cameroonians.”

Today, Malu, Naseri and Tajoah stand as examples of redemption. Once armed with rifles, they now wield pens and lesson plans, urging young people to claim their future through education.

“It will be good if the United Nations can help most of these former fighters to return to school. I have spoken to so many who want to go back to school but lack the means,” Malu says.

“The people I used to fight alongside are still enforcing lockdowns and blocking children from learning,” says Tajoah. “Even if they have to fight, let children go to school, it is their basic right. We must not disturb children’s education.”

Cameroon will elect a new president on October 12. Incumbent Paul Biya, 92, who has ruled the country since 1982 has promised to “strengthen peace and unity” if he wins his 8th term.

“Paul Biya has failed to solve the separatist conflict. But if he wins, this will be his last chance of redemption, for the next seven-year-mandate, to solve this separatist conflict once and for all,” says James Mbah, a political analyst. “Former separatist fighters who are now returning to school is a clear opportunity for peace and reconciliation. Whoever wins the election can capitalize on that to end the conflict and most importantly ensure children study in safety in the Anglophone regions.”

This article was published on September 30, 2025 at 18:52, and updated on October 4, 2025 at 12:00. Part of this investigation was first published by Xinhua News Agency.