When gunfire first echoed through their village in the South West Region of Cameroon, little Christabel ran into the lush bushland with her mother, clutching the rough book she had used the previous night to practise spelling. Eight years later, she still keeps that same rough book — now dog-eared, yellowing, and filled with hopes suspended.

“I was in Class One when school stopped,” she says quietly. “I didn’t understand why. I just wanted to learn.”

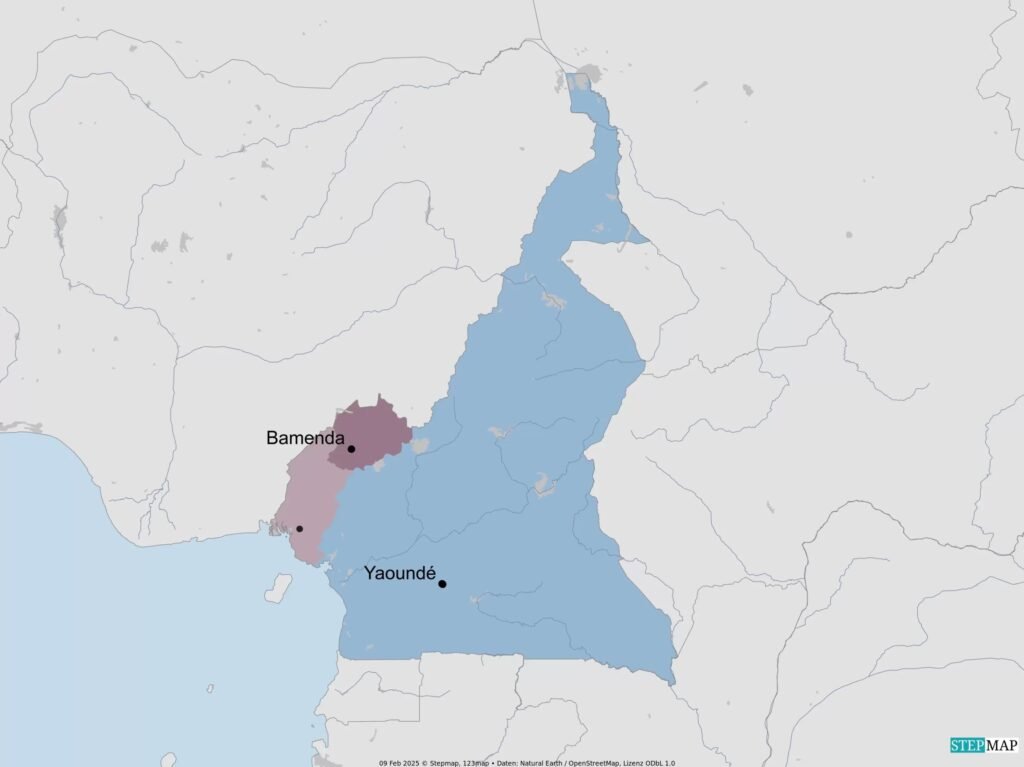

Christabel is one of nearly half a million children aged between three and 17 whose education has been severely disrupted by the drawn-out Anglophone crisis — now in its ninth year. According to a 2024 assessment report by the Cameroon Education Cluster, 2,066 schools, corresponding to 41% of schools across the restive North West and South West regions are not functioning; they have either remain closed, destroyed, abandoned or occupied by the belligerent forces.

Some learners have not entered a classroom since 2016 when the crisis erupted as low-level protests by English-speaking teachers and lawyers against the imposition of French in their schools and courts by the Francophone-dominated government. Many more have grown from early childhood into adolescence without ever receiving foundational literacy, numeracy, or the social development that school naturally provides.

Behind every statistic lies a childhood turned upside down. Teachers displaced. Families uprooted. Dreams deferred.

Yet, in the heart of communities still grappling with insecurity and where children and their caregivers have fled to for safety, an ingenious model of learning is taking root — small, colourful, and profoundly transformative.

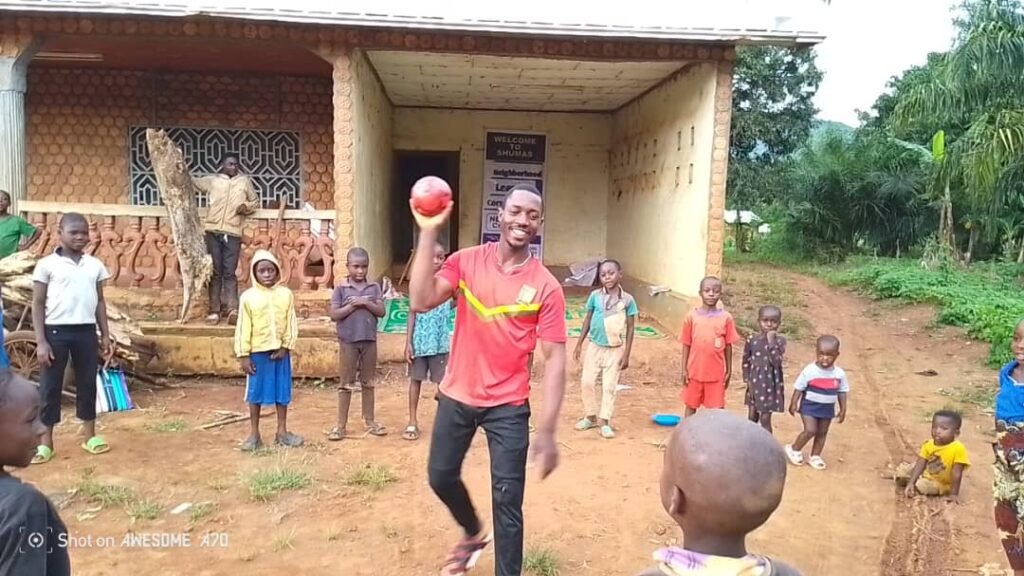

Photo courtesy of Street Child Cameroon

In 2021, humanitarian organization Street Child, working with several local partners, quietly launched a bold educational experiment: mobile inclusive neighbourhood learning corners—grassroots, community-run learning spaces set up within minutes of children’s homes or wherever they can safely gather. The concept is elegantly simple: As children cannot safely reach school, education must then reach them wherever they are.

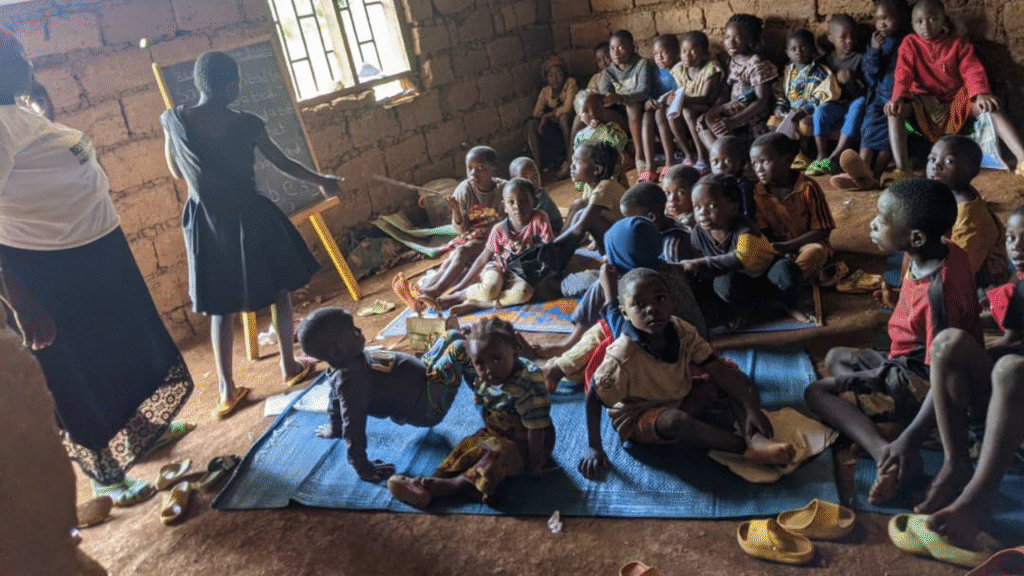

“It is in the chiefs’ palaces. It is in the communities. They sit on the mat, learn and play together. That puts them in the right frame of mind to start learning again,” explains Dr. Alfonce Tata Nfor, Country Director of Street Child UK Cameroon. He says the learning corners are not just stopgap solutions but lifelines through which learning can continue even when everything else has fallen apart.

According to Nfor, all the teachers are trained to handle crisis-specific children because their circumstances are different. “If you shout in the classroom, what they will hear is the gunshot, not the shouting,” he tells NewsWatch.

The corners are developed from whatever the community can provide — tents, repurposed structures, verandas, or shaded compounds. They are staffed by trained community facilitators and volunteers who run small classes throughout the week, ensuring children receive individual attention and a stable routine.

According to facilitators, the children benefiting from the initiative are highly motivated, often arriving well before sessions begin and staying long after closing time. Many attend after helping their parents on the farm, some with younger siblings strapped to their backs.

“The children are hungry to learn after the trauma they’ve endured because of the conflict. At first, they were not very engaged, but once we introduced TaRL (Teaching at the Right Level), most of them became much more committed,” says Ngapu Aliyu, a facilitator at a SHUMAS learning corner in Ndokong II Community in Babessi, North West Region. “These children have been waiting for years. Now, they finally have a place to start again.”

Aliyu says he feels deeply fulfilled by the work he does. He recounts the case of one of his 37 learners who had been severely traumatised after losing both parents in an arson attack. “He [nine years old] never felt comfortable being around others,” Aliyu explains. “But now he is doing well and living with his maternal aunt.”

Taking education to doorsteps

For children like Christabel, the corners offer far more than basic academics. They restore normalcy to lives punctuated by fear, uncertainty and gratuitous violence. Each corner is designed to meet the wide range of needs that children in crisis settings face.

In addition to reading and numeracy lessons, facilitators incorporate play-based early childhood development activities that encourage creativity, curiosity, and social bonding. Psychological first aid and simple counselling techniques are woven into daily routines, giving children safe avenues to express emotions they have long bottled up.

Life skills such as hygiene awareness, communication, and cooperation are taught alongside academic content, enabling children to develop holistically. The corners also emphasize inclusion, ensuring children with disabilities or other vulnerabilities are not left out. Learning materials include brightly coloured storybooks, locally crafted toys, slates, chalk, and tactile tools suitable for learners with visual or cognitive challenges.

The intention is to make learning part of children’s everyday lives again, according to facilitators. Since the corners are situated inside neighbourhoods, often within sight of children’s homes, families do not have to worry about long journeys or unsafe roads. When families relocate because of insecurity, facilitators can quickly re-establish a corner in the new settlement, making the model responsive to the constantly shifting realities of conflict.

Neglected crisis of lost early childhoods

Cameroon, which has repeatedly featured on the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC)’s list of the world’s most neglected displacement crises, now tops the ranking. According to the NRC, those with the power to respond to the country’s overlapping emergencies have largely overlooked the plight of affected communities, especially children and women, whose suffering rarely makes international headlines. These vulnerable persons receive little to no assistance, and their crises seldom attract the diplomatic attention or humanitarian mobilisation seen elsewhere in the world.

The crisis has created a generation of children whose earliest memories are shaped by lockdowns, displacement, fear, kidnap, torture and killings. Over 6,500 people have been killed since 2017 as a result of the bloody war between armed separatists and government troops, according to International Crisis Group estimate. In one instance in October 2020, gunmen stormed a school in Kumba and opened fire indiscriminately, killing at least six children and wounding several others.

The impact on early childhood development is particularly alarming. A briefing note by Moving Mind Alliance shows that children who miss early learning opportunities between ages three and six are significantly more likely to struggle later in school, drop out, or face lifelong socioeconomic disadvantages. In conflict settings such as Cameroon’s North West and South West regions, these risks multiply.

Children out of school are far more likely to be exposed to recruitment by ‘Amba Boys’ (as the armed separatists are commonly known) or abused in the society. Girls face heightened threats of early marriage, exploitation, and domestic labour. Children with disabilities often experience double exclusion, kept indoors not only because of insecurity but also because of stigma and lack of accessible learning environments.

“We are raising a generation who have never known normal school life,” says Wanatu Agnes, a seasoned educator who ran 34 safe places for children in Meme Division, South West Region. “Education cannot wait. The children who were not able to flee from the crisis areas benefited from the safe places,” she recounts, noting that without urgent intervention, the long-term human capital losses will be devastating.

A community-built solution

What distinguishes the neighbourhood learning corners from traditional education interventions is their deep community ownership as every member plays an active role. They help source spaces, construct temporary structures, mobilize learners, and support facilitators. This shared responsibility means that the model does not collapse when external actors leave; instead, it becomes embedded in the community fabric.

The initiative also supports children’s transition into formal education through structured reinsertion programmes. After completing remedial learning sessions and undergoing assessments to determine their academic levels, learners are placed into public schools where fee-waiver agreements have already been secured. They also receive essential learning materials, including books and pencils, to help them integrate smoothly and continue their education.

Billian Nyuykighan, Director General of Strategic Humanitarian Services (SHUMAS), a local development and humanitarian organization which runs learning corners in Babessi, Galim and Banza, says beyond transitioning kids to formal education, they also train their parents on income-generating activities to ensure sustainability.

“This enables the parents to be able to have a steady income so that they can take over the task of sponsoring their kids going forward,” she tells NewsWatch, adding that they encourage parents to come together as a group and form village saving and loans scheme from which they can turn to in times of need.

Parents, many of whom have been unable to afford transportation costs, uniforms, or tuition during the years of conflict, see the corners as a blessing.

“My child used to stay at home and roam around the neighbourhood. I used to get a lot of complaints about her causing trouble,” says Caroline Ziawung, an IDP from Zhoa now living in Galim. “But the learning corner has changed things. I now have control over her. Whenever she comes home, she brings an assignment that keeps her busy.”

Local leaders echo this sentiment, viewing the corners as a bridge between crisis and eventual recovery. They note that while formal schools remain inaccessible in some areas, the learning corners allow children to remain engaged academically and socially until peace and reconstruction allow for a return to traditional schooling.

Reigniting the joy of learning

In a learning corner in Lebialem Division, the atmosphere resembles a cheerful campsite. Children gather under a tarpaulin decorated with hand-drawn images of suns, trees, and the alphabet. A facilitator leads a lively phonics game while children take turns shouting out sounds and cheering for one another.

“When I teach them to write their names, they glow with pride,” says facilitator Ateh John. “They feel seen.”

Play-based learning is particularly transformative for younger children, many of whom were too young to attend school before the crisis broke out. Colour blocks, songs, storytelling, and movement activities stimulate cognitive and emotional development. Older children practise reading short passages, solving basic arithmetic problems, and engaging in group discussions. A quiet corner at each site is reserved for emotional support, allowing children who have witnessed violence or loss to speak privately with trained facilitators.

Early monitoring shows encouraging results. Many learners who had never held a pencil or recognized letters are now reading simple words within months. Parents have expressed astonishment at their children’s rapid progress.

“When I read for the first time, my mother cried,” recalls 13-year-old Atemafac. “She thought I would never learn.”

Financing innovation at scale

Despite their simplicity, the learning corners require seed funding to thrive. Facilitators need stipends and continuous training. Materials such as chalk, storybooks, mats, and child-friendly tools must be replenished. Communities also need basic infrastructure to ensure safety and consistency. Although these costs remain minimal compared to school construction or teacher deployment, they are crucial for sustaining quality.

Research consistently shows that investments in early childhood development deliver among the highest returns in global education, with some studies estimating social and economic benefits of up to $13 for every dollar invested. In crisis settings, the return is even higher because early learning interventions help children avoid long-term developmental delays.

Yet education remains one of the most underfunded sectors in humanitarian response plans for Cameroon. The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs’ Financial Tracking Service data show that just about 6% of required funding was secured for education. This gap underscores the urgent need for donors, philanthropies, and government actors to support scalable, cost-effective models like the learning corners.

“We’re demonstrating that with modest, flexible funding, community ingenuity can solve problems once considered impossible,” says one project official who preferred not to be named. “But to reach all children in need, we must scale.”

Street Child’s project has established over a hundred of learning corners across communities in the North West, South West, Littoral, Centre, East and South regions. The organization hopes to double its reach, prioritizing areas with high displacement, communities without functional schools, and neighbourhoods hosting large numbers of out-of-school children.

To date, more than 25,000 children have benefited from foundational literacy and numeracy instruction, structured learning support, and access to critical learning materials, according to Street Child officials.

“The steps taken are commendable. We still have some areas where schools are not going on. If you people [NGOs] can reach there and do what you are doing, then it is good for us,” says Elangwe Rose Bume, South West Regional Delegate of Basic Education. “They [NGOs] have been of great assistance,” she underscored, adding that the model aligns with government’s pre-school vision.

On a warm afternoon, Christabel sits cross-legged at her learning corner, tracing the letter “M” on her slate with bright white chalk. The facilitator leans in, offering gentle correction. Her eyes shine — not with fear, but determination.

“When the crisis ends,” Christabel says, “I want to be a teacher. I want to teach children like me.”

Her dream, once derailed by violence, is alive again.

Across Cameroon’s conflict-affected regions, thousands of children share that renewed sense of possibility. Each neighbourhood learning corner represents a tiny victory: a reclaimed childhood, a restored pathway, a promise kept.

The mobile inclusive neighbourhood learning corners has demonstrated what is possible when innovation, local ownership, and compassionate funding intersect. But with about half of schools still closed and close to half a million children in need of immediate support, the journey has only just begun.

For Christabel and thousands like her, the learning corner is more than a temporary school. It is a declaration that even in crisis, their futures still matter. And that learning, no matter the circumstance, must always find a way home.

****

This story was produced with support from the Moving Minds Alliance (MMA) through the Reporters for Early Age Children in Crisis (REACH) Advocacy Stories Fund.