At the She Leads Africa Summit’s launch in Nairobi on Monday, August 11, UN Director-General in Kenya Zainab Hawa Bangura delivered an urgent call to action: “Educating a girl is educating a community. You have to set the agenda; if you don’t, you become the menu—they will eat you up dry.” Drawing from her own escape from child marriage, Bangura urged African governments to back promises with budgets that elevate girls into leadership roles.

This plea echoes across the continent. In Kenya, only 23.3% of parliamentary seats are held by women; Uganda fares slightly better at 33.9%; Malawi and Madagascar lag behind at 23% and 18.5% respectively. Despite billions of dollars in development aid, these figures remain stagnant.

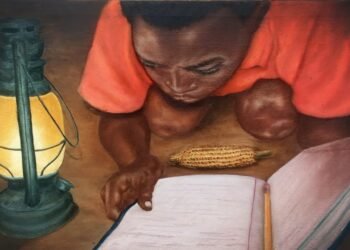

According to UNICEF, West and Central Africa face the highest child marriage prevalence globally—with around 41% of girls marrying before 18, and countries like Niger (76%), Central African Republic (68%), and Chad (67%) among the worst affected. Nigeria alone accounts for 22 million child brides—40% of all cases in the region. In Mali, over half of women aged 20–49 were married before 18, and 15% before 15. These staggering statistics are more than numbers—they represent lost education, stunted potential, and cycles of poverty.

Kenya’s Principal Secretary for the State Department for Parliamentary Affairs Aurelia Rono echoed Bangura’s message, recalling Kenya’s own transformation—from a time when women couldn’t hold ID cards independently to the present, where nearly 30% of Principal Secretary roles are filled by women.

“When you succeed, you open the door for others,” Rono said.

Her message applies equally to West African contexts—where Senegal recently elected a woman to its national parliament and Ghana welcomed its first female vice-president in 2024.

Magdalane Muoki, Country Director of Terre des Hommes Kenya, urged that the Summit be more than a symbolic gathering:

“Girls are not just tomorrow’s hope—they are today’s reality. It’s time to fund, protect, and amplify their leadership.”

In Niger, where child marriage affects up to 76% of girls, local youth networks are mobilizing rural communities to delay marriage and promote schooling. In Mali, grassroots activists in Sikasso and Kayes regions are educating families about legal marriage age and girls’ rights. In Nigeria, where the number of child brides is staggering, activists are using social media and radio to challenge stigma and change expectations in slums and villages.

Bangura emphasized that legal frameworks—from the Maputo Protocol to the AU Convention on Ending Violence Against Girls and Young Women (CEVAWG)—must translate into funded policies.

“We have the resolutions. Now we must ask: what laws are enforced? What policies are funded? What practices are changing on the ground?”

For countries like Kenya, Uganda, Malawi, and Madagascar, where gender gaps manifest differently across urban and rural areas, the message is clear: transformative change is urgent—and possible.

As delegates prepare for the summit’s next days of workshops and strategy sessions, their challenge remains: turn expensive rhetoric into tangible reform. From ensuring pregnant girls return to school, to budgeting safe spaces, to enacting and enforcing protective laws—Africa must invest in its girls today—for them are leading the way.

“When girls lead, Africa thrives,” said Muoki. And with the evidence mounting—from West to East—Africa’s future depends on whether leaders—and citizens—will act now.